HFT Engine Latency - 5: Thread Spinning

Burn your CPU, not your PnL

Introduction

Previous articles in this Apex latency series have generally focused on one optimisation at a time, from hardware tuning to software design. Each article introduced a specific technique and presented experiments measuring its impact on tick-to-model latency.

However, one particular technique found its way into the code base without receiving the discussion it deserves.

In this article, we isolate that technique - thread spinning - and examine it in detail. We explain what thread spinning is, why it is commonly used in low-latency trading systems, and measure the benefits it provides in practice.

What is spinning

Thread spinning is a simple technique that gives an immediate kick in performance.

In software design we often have situations where a thread must wait for an event to occur, or for some condition to become true. Examples include waiting for market data to arrive on a socket, waiting for user input, or waiting to acquire a mutex. The default behaviour is to suspend the waiting thread: the kernel puts the thread to sleep until the event or condition occurs, at which point the thread is resumed and execution continues.

Spinning is an alternative to this default behaviour. Instead of being suspended, the thread remains runnable and spins in a tight loop, repeatedly checking whether the condition has become true. As soon as it does, the thread continues immediately on to its work.

The main benefit of spinning is that it avoids the suspend-resume transition entirely. This is critically important for HFT systems, because resuming a suspended thread can easily take several to tens of microseconds - enough to completely blow a tick-to-trade latency budget.

However, spinning is not without its drawbacks. A spinning thread consumes an entire CPU core, driving utilisation to 100%, effectively preventing other code from using that core, and increases power consumption. For this reason spinning cannot be used everywhere and at all times. Its use is necessarily selective, typically reserved for handling latency critical paths, or employed only briefly, as in the case of spinlocks.

Spinning in Apex

The Apex trading engine includes optional support for thread spinning. When enabled via runtime configuration, the IO thread responsible for reacting to market data can be made to spin, rather than being suspended by the kernel.

The implementation is straightforward. Apex uses the system call poll to detect when data is available on a socket. If no data is ready, which is most of the time, poll normally suspends the calling thread for the duration of the specified timeout. Alternatively, poll can be invoked with a timeout value of 0, which causes it to return immediately if no data is available. The following line shows how, if suitably configured, the value of 0 is passed to poll.

n = poll(&fds[0], fds.size(), _config.spin ? 0 : timeout);

Spinning behaviour - passing 0 as the timeout parameter - is controlled by Apex engine instance configuration. Being able to configure this behaviour is important: spinning trades CPU resources for lower latency, and is therefore appropriate only for strategies that genuinely require every ounce of performance.

When 0 is passed to poll and no data is available at the socket, the call returns immediately. The IO thread then continues into the event loop, checking for expired timers or closed sockets, before executing the poll sequence again. In this fashion poll is repeatedly invoked, without delay or suspension, until data becomes available. At that point, the socket is read, raw market data bytes are retrieved, and the inbound processing stack proceeds to SSL decoding, protocol parsing, and subsequent processing stages.

Experiments

To examine how thread spinning affects latency, Apex was run in both spinning and non-spinning modes, and the total tick-to-model latency was measured and compared. As in previous experiments, the test system was a 3.40 GHz Intel Core i7, with C-states and P-states configured for minimum latency (as described earlier in this series, here).

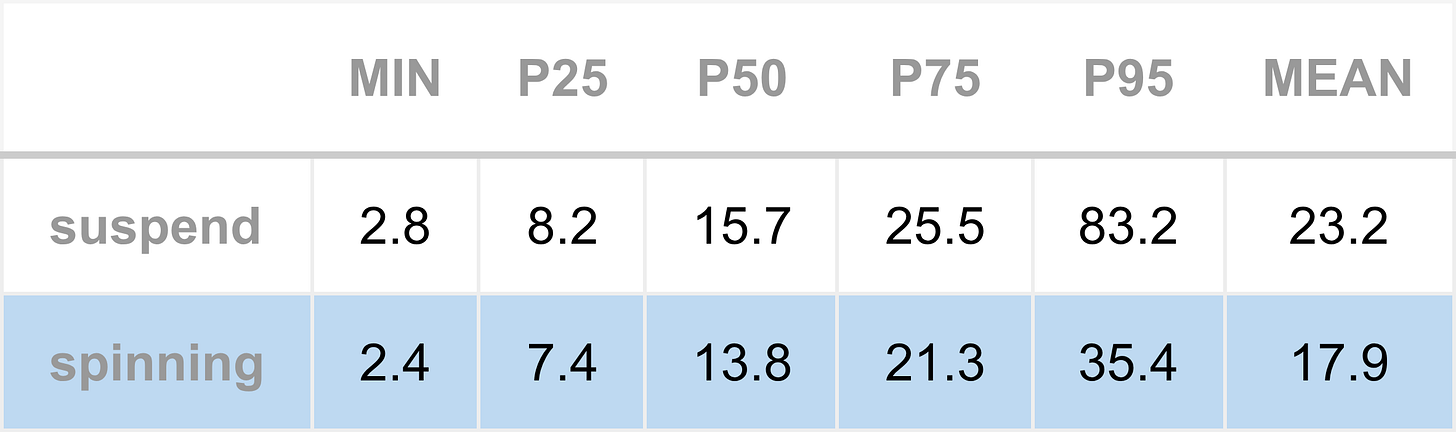

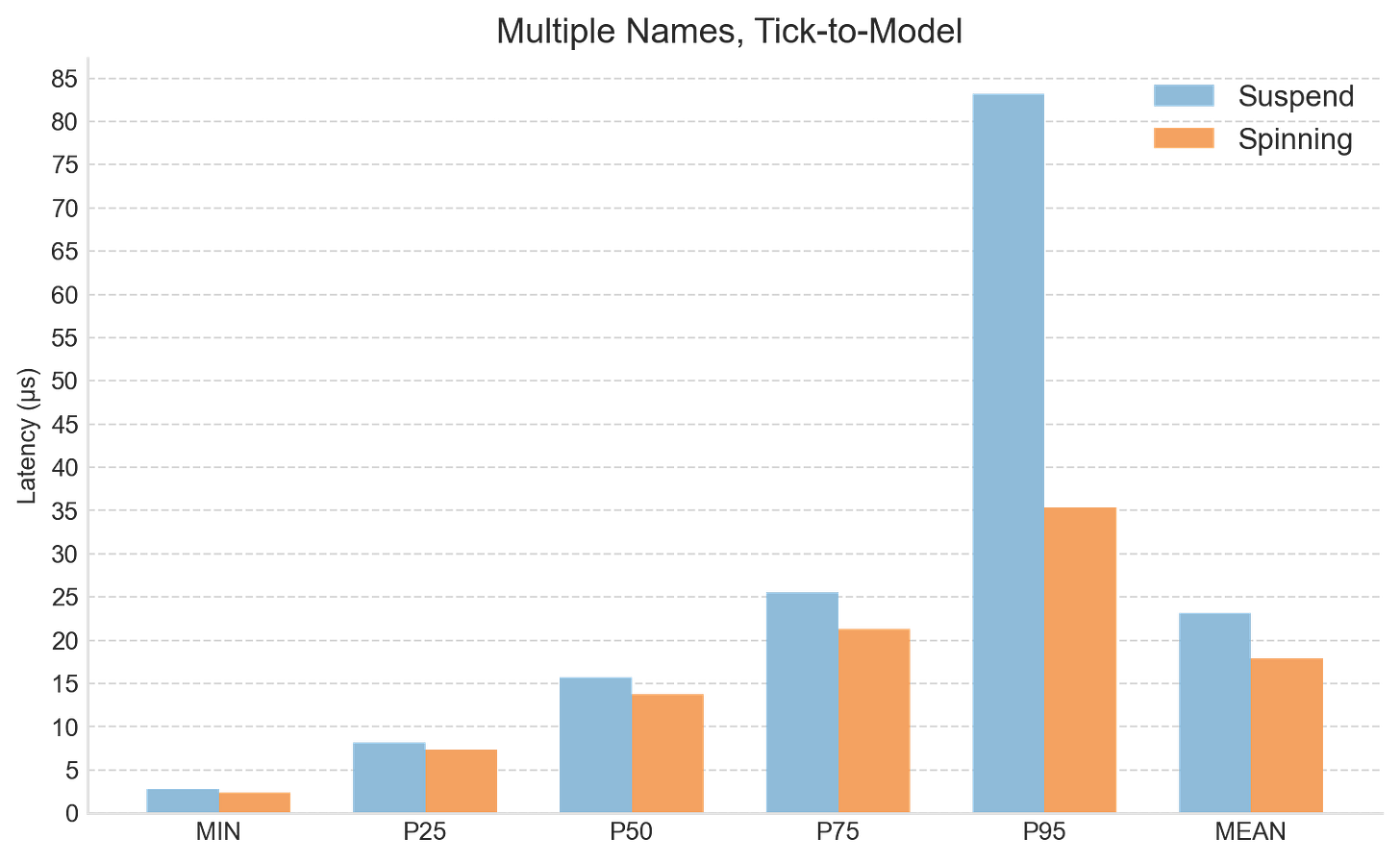

For the first experiment, Apex was configured to subscribe to four instruments, creating a moderate and sustained load. The table below shows percentile breakdowns for the total tick-to-model path. The same data is also presented graphically in the accompanying bar chart.

The results show a small but consistent reduction in latency across all measured percentiles, a notably clean result. The improvement at the minimum, approximately 0.4 microseconds, may appear modest, but it is meaningful in the context of HFT tick-to-trade budgets, which typically target well under 10 microseconds. Importantly, this reduction is not confined to the minimum: similar improvements are observed across the higher percentiles.

Some caution is required when interpreting the improvements at the higher percentiles. Measurements here are influenced by message queuing effects, which in turn are driven by the particular market data rates that existed during the experiment. Nevertheless, the improvements are encouraging and are in the right direction.

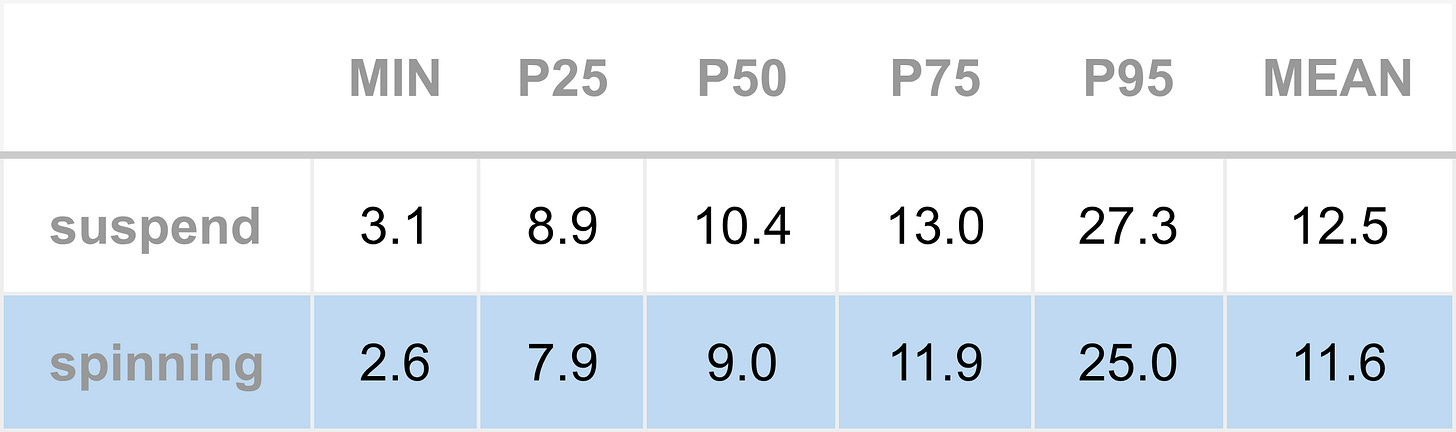

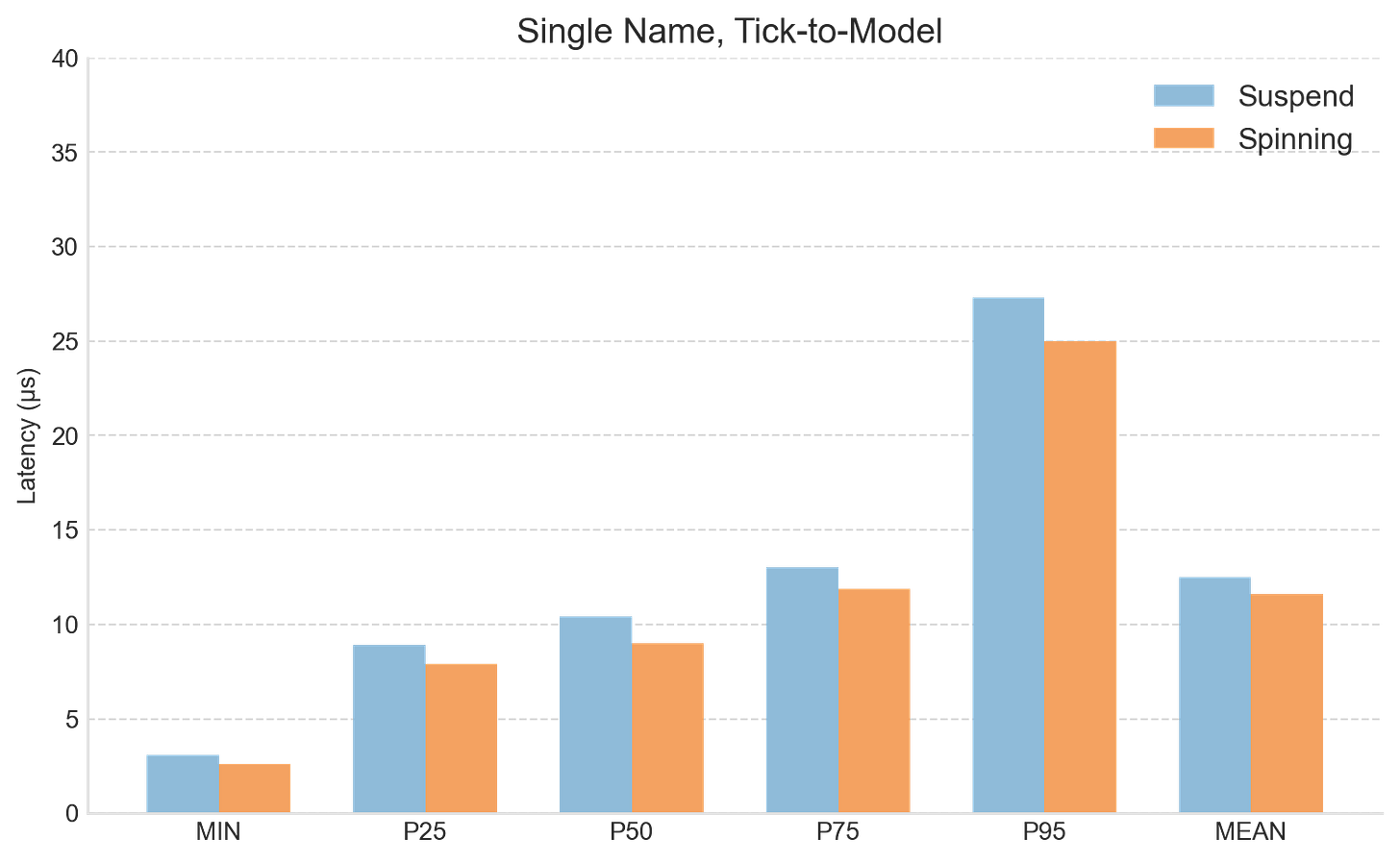

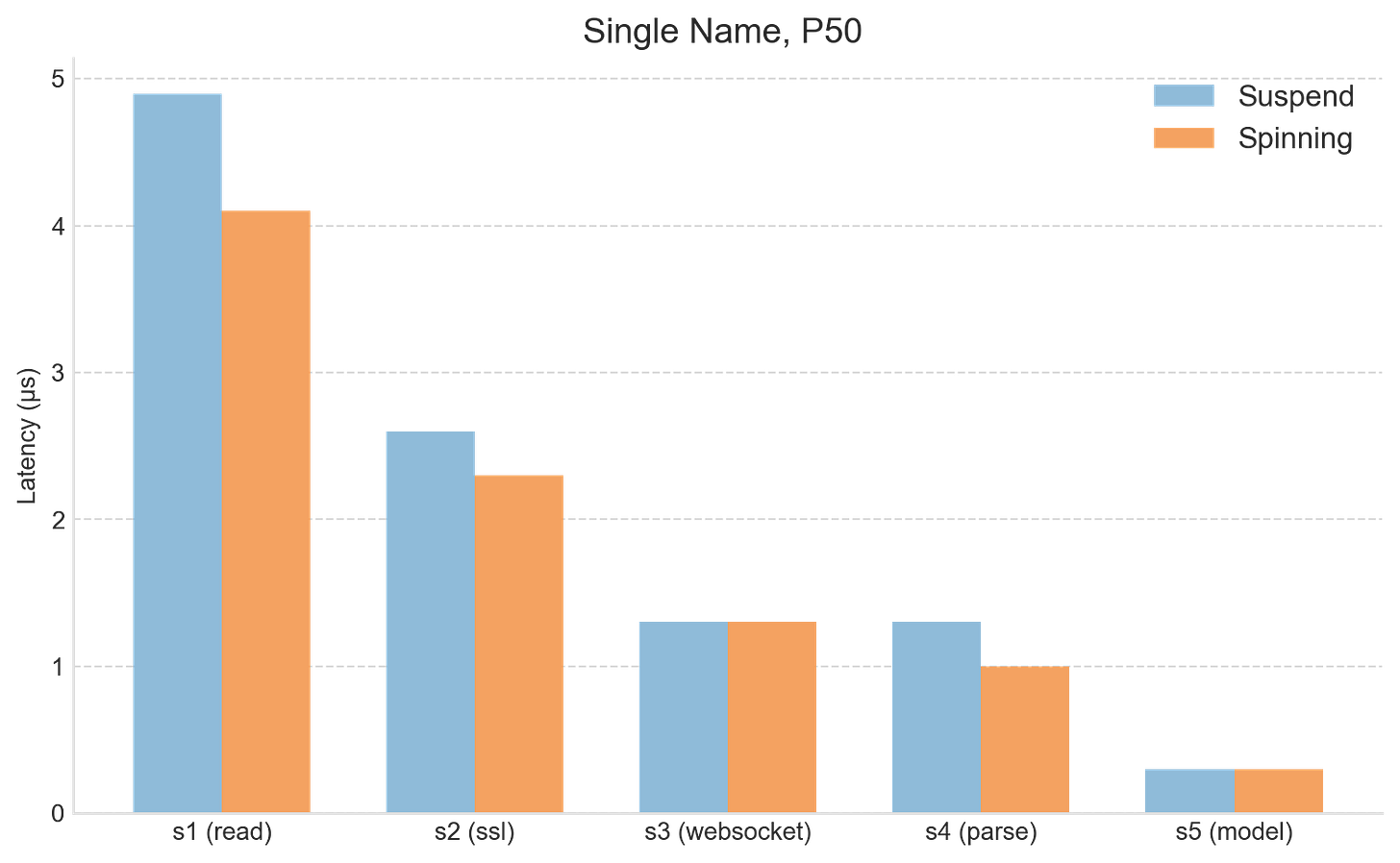

In the second experiment, Apex was configured to subscribe to a single instrument. This replicates the deployment pattern when targeting the lowest possible latency and therefore provides the clearest view of Apex’s baseline performance.

The results are shown in the next table and accompanying chart.

As before, a similar reduction is observed at the minimum, of approximately half a microsecond. And once again, this improvement is carried into the higher percentiles, with median (P50) latency improving by around 1 microsecond.

Across both experiments the tick-to-model latency improved by approximately half a microsecond. This naturally raises the question: where does this improvement come from?

To investigate this, the milestone latencies for the single-instrument P50 results are compared in the following chart. We can seen that the reduction is concentrated almost entirely at the socket IO stage. This is expected, because it’s precisely during this stage where a thread would otherwise be suspended and later resumed, incurring wake-up latency.

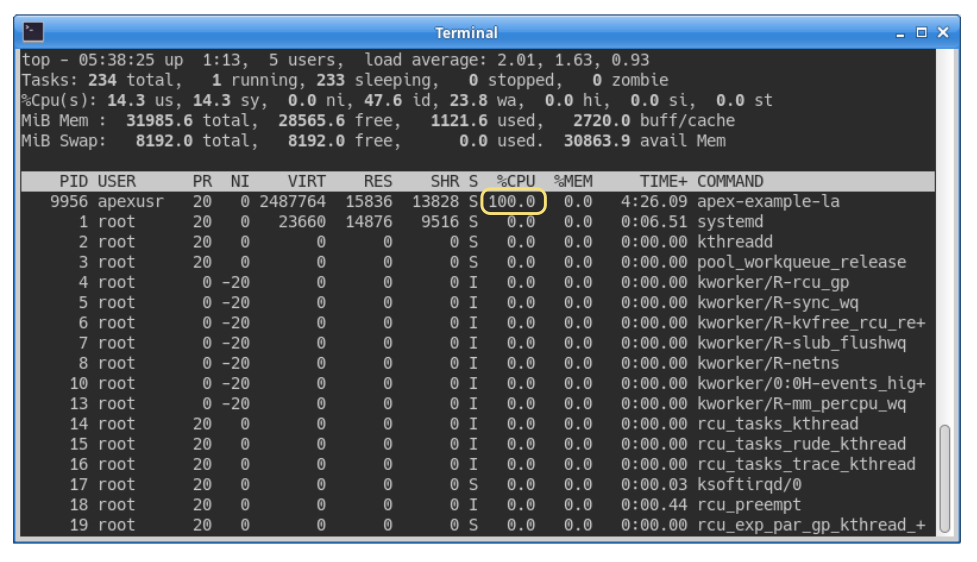

As noted earlier, spinning comes with the drawback of high CPU consumption. This is illustrated in the following screenshot, which shows system load while Apex was running in spinning mode. The %CPU column shows the engine now fully consumes a logical CPU, remaining near 100% at all times.

Summary

Thread spinning is like a shot of adrenaline for a trading system - a small, targeted change that delivers a noticeable and consistent performance boost.

Introducing spinning is straightforward, often requiring just a few additional lines of code. It can be applied whenever a thread needs to wait for data, or more temporarily when acquiring locks. In Apex, we added spinning to the socket IO stage to reduce the time taken to react to market data.

Experiments demonstrated a significant and consistent benefit. Tick-to-model latency improved by around half a microsecond at the minimum, and persisted across higher percentiles. This is meaningful in the context of low-latency trading, where microseconds matter. The improvement arises from avoiding thread wake-up delays and, secondarily, from keeping relevant state hot in the CPU cache.

Not every HFT engine needs thread spinning, but for deployments targeting the lowest possible latency, its immediate benefits make it a strong recommendation.

However, spinning is not without trade-offs. A spinning thread fully consumes a logical CPU, increasing power usage and potentially preventing other threads from running efficiently. For this reason it must be carefully controlled: multiple spinning threads should not contend for the same physical core, hyper-threading should be disabled, and spinning should be reserved for the critical path only.

While adding spinning to Apex was initially straightforward, there are further refinements to consider.

First, spinning threads should be pinned and isolated to dedicated cores to prevent latency jitter due to thread migration or interference from other user or kernel threads.

Second, the spin loop itself should be as minimal as possible. In the current Apex IO reactor, the loop includes timer checks and socket cleanup, in addition to the polling logic. Such housekeeping activities could potentially be moved out of the hot path, reducing the amount of code within the loop. Additionally, while spinning on poll() already yields significant gains, alternative approaches, such as epoll or other IO mechanisms, may allow for more efficient spinning.

These improvements, along with other spinning patterns such as spinlocks, are topics for future exploration as we continue the Apex latency optimisation journey.